Warning

This documentation will no longer be mantained. The official FARGO3D repository is now https://github.com/FARGO3D/fargo3d, and the documentation is https://fargo3d.github.io/documentation/

Outputs¶

FARGO3D has many different kinds of outputs, each one with different information. They are:

Scalar fields.

Summary files.

Domain files.

Variables file.

Grid files.

Legacy file.

Planetary files.

Monitoring files.

This section is devoted to a brief explanation of each kind of files

Scalar fields¶

These files have a .dat extension. They are unformatted binary

files. The structure of each file is a sequence of doubles (8 bytes),

or floats (4 bytes) if the FLOAT option was activated at build time

(see the section .opt files). The number of bytes stored in a field

file is:

\(8 \times N_x\times N_y\times N_z\)

\(4\times N_x\times N_y\times N_z\) if the option FLOAT was activated.

Remember that \(N_x\), \(N_y\), \(N_z\) are the global variables “NX NY NZ” defined in the .par file (the size of the mesh).

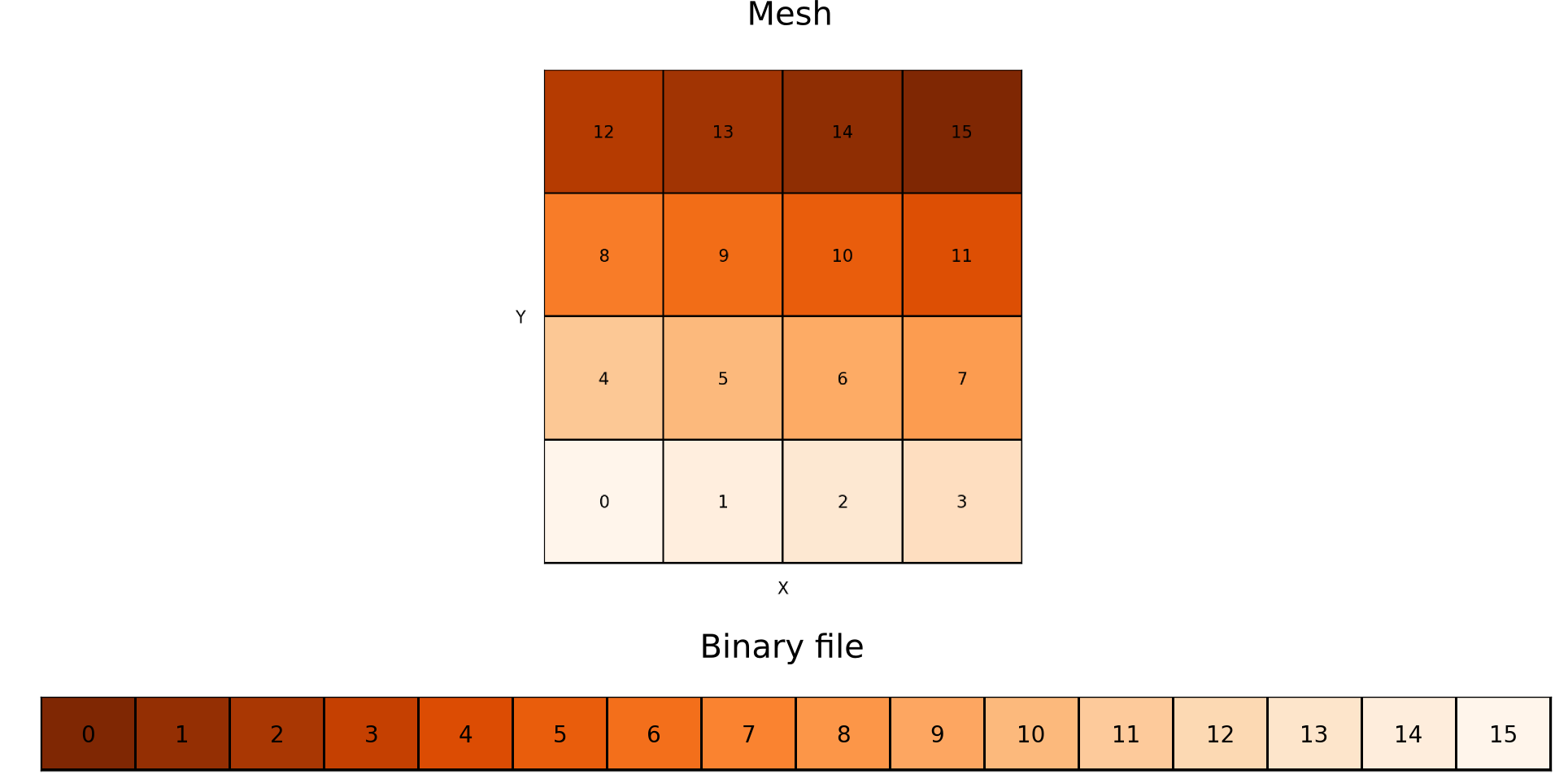

For a correct reading of the file, you must be careful with the order of the data. The figure below shows how the data is stored in each file (for 2D simulations, but the concept is the same in 3D).

The fast (“innermost”) index is always the x-index (index i inside the code). The next index is the y-index (j) and the last one is the z-index (k). If one direction is not used (eg: 2D YZ simulation), the indices used follow the same rule. Note that scalar fields files do not contain information about coordinates. It is only a cube of data, without any additional information. The coordinates of each cell are stored in additional files, called domain_[xyz].dat (see the section below).

When you use MPI, the situation becomes more complex, because each

processor writes its piece of mesh. If you want to merge the files

manually, you need the information of the grid files, detailed

below. In practice, all the runs are done with the run time flag

-m (merge), in order to avoiding the need for a manual merge. If

your cluster does not have a global storage, you have to do the merge

manually after having copied all files to a common directory.

The fields may be written with a different output format, called VTK-format. This format is a little bit more complicated and is discussed in the VTK section.

Here you have some minimalist reading examples with different tools (additional material can be found in the First Steps section and in the utils/ directory):

c:

FILE *fi;

double f[nx*ny*nz];

fi = fopen(filename, "r");

fread(f,sizeof(double), nx*ny*nz, fi);

fclose(f);

python:

from pylab import *

rho = fromfile("gasdens120.dat").reshape(nz,ny,nx)x

GDL or IDL:

GDL> openr, 10, 'gasdens10.dat'

GDL> rho = dblarr(nx,ny)

GDL> readu, 10, rho

GDL> close, 10

fortran:

real*8 :: data(nx*ny*nz)

open(unit=100, status="old", file=filename, &

& form="unformatted", access="direct", recl = NX*NY*NZ*8)

read(100,rec=1) data

gnuplot:

plot filename binary format="%lf" array=(nx,ny) w image

Summary files¶

Every time FARGO3D outputs coarse grain scalar fields, a

summary[i].dat file is written to the output directory (where

[i] stands for the output number). This file contains the

following information:

A section indicating the setup, the code version, the mesh size and geometry, the number of outputs scheduled, the number of planets (if any), and (if the sticky flag

LONGSUMMARYis defined) the filename of the source tar file. The latter is made at build time and consists exclusively of the sources found in the VPATH used for the build. This archive is copied to the output directory upon the run start. Its naming convention issources[n].tar.bz2, where[n]is the smallest integer for which no such file name exists in the directory. Therefore, upon a fresh start in a new directory, the archive name will besources0.tar.bz2. If a restart is issued, the subsequent archive file will besources1.tar.bz2so as to not overwrite the previous source archive (the source may have changed between the initial run and the restart). The source archive may be expanded using the commandtar jxvf source[n].tar.bz2, and it expands in a subdirectoryarch/.A section giving the full set of compilation options of the code.

A section giving the list of the sticky build flags (only if the sticky flag

LONGSUMMARYis defined).A section giving runtime information such as the directory from which the run was launched, the command line used, the parameter file, the number of processes and the host names, together with the corresponding rank (and device number for GPU builts).

A section indicating the time at which the output is performed.

A section indicating the different preprocessor macros known to the code.

A section listing all the parameters known to the code, in alphabetical order. This includes not only those declared in the parameter file, but also those which do not appear in that file and have a default value.

A section giving the full content of the parameter file. This section should in most cases be redundant with the previous section, but the value of some parameters may evolve during execution.

A section containing the boundary conditions used in the build (only if the sticky flag

LONGSUMMARYis defined).For the runs which involve at least one planet, a section listing the 3 components of each planet position and velocity, as well as its mass, and a copy of the planetary system configuration file.

Note

In order to keep the source archive and executable in sync, we

append trailing information directly to the executable binary file

(namely, among others, a tar file of the source), at build time

(only if LONGSUMMARY is defined). Copying the source files to

the output directory to keep a track of the code used to generate a

given data could be misleading if the user edits the source but

does not recompile the code. Our method is therefore more robust,

but more involved. It works fine on a variety of

platforms. However, it requires opening the executable file itself

as an input stream during execution. This requires that the OS

allows this type of operation, and that the correct full path to the

executable is properly retrieved at run time. If you get the message:

Attempting to use an MPI routine before initializing MPI Cannot open executable file to retrieve information appended.

you should check the value of the variables

CurrentWorkingDirectory and FirstCommand in

src/summary.c, and fix them accordingly. In order to avoid

potential problems, by default we have deactivated all logging

which requires interfering manually with the executable (namely

logging the source tar archive, the sticky flags used at build time

and the set of boundary conditions). If you want to log this

information, you must build FARGO3D with the sticky flag

LONGSUMMARY=1. Since the possibility of having long summaries

is essentially platform dependent (rather than setup dependent),

you may want to change the default behavior by editing the file

std/defaultflags.

Note

Even if the sticky flag LONGSUMMARY is not activated, a

subdirectory named arch/ is produced in FARGO3D’s main

directory, which contains all the source effectively used to build the

code. This includes all the boundary conditions C files derived from

the setup, the CUDA files in case of a GPU build, etc. This directory

can be copied for your records to the output directory by your batch

scheduler.

Domain files¶

Another important piece of output is the domain files:

domain_x.dat

domain_y.dat

domain_z.dat

These three files are created after any run, except if they existed in

the output directory before running your simulation. The content of

these files are the coordinates of the lower face of each cell

([xyz]min inside the code). They can also be considered as the

coordinates of the interfaces between cells. It is important to note

that domain_[yz].dat are written with the ghost cells. The

format is ASCII, and the total number of lines is:

domain_x.dat: Nx lines

domain_y.dat: Ny+2NGHY lines

domain_z.dat: Nz+2NGHZ lines

where NGHY=NGHZ=3 by default. The active mesh starts at line 4 and has Ny+1/Nz+1 lines (up to the upper boundary of the active mesh).

If you want to use a logarithmic spacing of the domain, you could set

the parameter Spacing to log (see the section “Default

parameters”). If you include in the output directory files with the

name domain_[xyz].dat, their content will be read, which enables

you to handcraft any kind of non-constant zone size.

Variables¶

When you run the code, two files called variables.par and

IDL.var are created inside the output directory. These files are

ASCII files containing the same information in two different formats:

the name of all parameters and their corresponding values. IDL.var is

properly formatted to simplifying the reading process in an IDL/GDL

script:

IDL> @IDL.var

IDL> print, input_par.nx

384

IDL> print,input_par.xmax

3.14159

The standard .par format is used in variables.par. It may be used again as the input parameter file of FARGO3D, should you have erased the original parameter file.

Grid files¶

One grid file is created per processor. Inside each file, there is information stored about the submesh relative to each processor. The current format is on 7 columns, with the data:

CPU_Rank: Index of the cpu.

Y0: Initial Y index for the submesh.

YN: Final Y index for the submesh.

Z0: Initial Z index for the submesh.

ZN: Final Z index for the submesh.

IndexY: The Y index of the processor in a 2D mesh of processors.

IndexZ: The Z index of the processor in a 2D mesh of processors.

For an explanation of the last two items, go to the section about MPI.

Planet files¶

These files are output whenever a given setup includes a planetary

system (which may consist of one or several planets). This, among

others, is the case of the fargo and p3diso setups. There are

three such files per planet, named planet[i].dat,

bigplanet[i].dat and orbit[i].dat, where i is the planet

number in the planetary system file specified by the parameter

PLANETCONFIG. This number starts at 0. For the vast majority of

runs in which one planet only is considered, three files are therefore

output: planet0.dat, bigplanet0.dat, and orbit0.dat. The

last two files correspond to fine grain sampling (that is, they are

updated every DT, see also Monitoring). In contrast,

planet[i].dat is updated at each coarse grain output (every time

the 3D arrays are dumped), for restart purposes. This file is

essentially a subset of bigplanet[i].dat.

At each update, a new line is appended to each of these files. In the

file bigplanet[i].dat, a line contains the 10 following columns:

An integer which corresponds to the current output number.

The x coordinate of the planet.

The y coordinate of the planet.

The z coordinate of the planet.

The x component of the planet velocity.

The y component of the planet velocity.

The z component of the planet velocity.

The mass of the planet.

The date.

The instantaneous rotation rate of the frame.

In the file

orbit[i].dat, a line contains the 10 following columns:

the date \(t\),

the eccentricity \(e\),

the semi-major axis \(a\),

the mean anomaly \(M\) (in radians),

the true anomaly \(V\) (in radians),

the argument of periastron \(\psi\) (in radians, measured from the ascending node),

the angle \(\varphi\) between the actual and initial position of the x axis (in radians; useful to keep track of how much a rotating frame, in particular with varying rotation rate, has rotated in total).

The inclination \(i\) of the orbit (in radians),

the longitude \(\omega\) of the ascending node (with respect to the actual x axis),

the position angle \(\alpha\) of perihelion (the angle of the projection of perihelion onto the x-y plane, with respect to the -actual- x axis)

Note that in the limit of vanishing inclination, we have

The information of column 7 is very useful to determine precession rates, whenever the frame is non-inertial. For instance, the precession rate of the line of nodes is given by \(d(\varphi+\omega)/dt\).

Note

The file(s) planet[i].dat are emptied every time a new

run is started. This is because these files are needed for a

restart, so we want to avoid that out of date, incorrect

information be used upon the restart. In contrast, lines accumulate

in the files orbit[i].dat and bigplanet[i].dat until those

(or the directory containing them) are manually suppressed.

Datacubes¶

All the primitive variables (density, velocity components, internal

energy density (or sound speed for isothermal setups), and magnetic

field components (for MHD setups) are written every NINTERM steps

of length DT (each of those being sliced in as many timesteps as

required by the CFL condition). The files are labeled first by the

fluid name (e.g. gas), followed by the field name, plus the output

number N: gasdensN.dat, gasenergyN.dat, gasvxN.dat,

gasvyN.dat, etc. If the SETUP is 3D, the vertical velocity will

also be written (gasvz). In addition, some selected arrays can be

written every NSNAP steps of length DT. These arrays names are

controlled by the boolean parameters WriteDensity,

WriteEnergy, WriteVx, WriteVy, WriteVz, WriteBx,

WriteBy, WriteBz. These allow the user either to oversample

one of these fields (e.g., for an animation), or to dump to the disk

only some primitive variables (by setting NINTERM to a very large

value and using NSNAP instead). The files created through the

NSNAP mechanism obey the same numbering convention as those

normally written. In order to avoid conflicts with filenames, the

files created through NSNAP are written in the subdirectory

snaps in the output directory.

Besides, the runtime graphical representation with matplotlib is

performed using the files created in the snaps directory.

MPI INPUT/OUTPUT¶

A routine to enable MPI Input/Output was implemented in the version 2.0. This Input/Output method should be used when running the code on several processes.

To activate this feature, use the option:

FARGO_OPT += -DMPIIO

In this case, the output files are labeled: fluidname_N.mpio. Each

of these files stores in raw format the domain of the mesh, the

density, the energy, and all the velocity components of the given

fluid. In addition, if the compilation option MHD is enabled, the

magnetic field components are written in the output file corresponding

to the fluid with Fluidtype = GAS. In the file

outputsfluidname.dat, the file position indicator for each scalar

field can be obtained.

To read the data from a .mpio file, a simple python script is

provided (see utils/python/reader_mpiio.py). Open a python terminal

(e.g. ipython ), import the script and execute the following lines

import reader_mpiio as reader

reader.Fields(output directory,"fluidname", output number).get_field("field name")

The possible name of the fields are dens for the density, vx,

vy and vz for the velocities and energy for the sound

speed in the isothermal case or internal energy density in the

adiabatic case.

Note

You can add fargo3d/utils/python to your

PYTHONPATH environment variable (in your .bashrc) to

make the script reader.py globally available from any

directory. You can also copy the script reader_mpiio.py

inside your current working directory.

Example:

from pylab import *

import reader_mpiio as reader

fluidname = "the fluid name goes here"

dens = reader.Fields("",fluidname, 0).get_field("dens").reshape(nz,ny)

imshow(dens,origin='lower',aspect='auto')

Monitoring¶

Introduction¶

FARGO3D, much as its predecessor FARGO, has two kinds of outputs: coarse grain outputs, in which the data cubes of primitive variables are dumped to the disk, and fine grain outputs, in which a variety of other (usually lightweight) data is written to the disk. As their names indicate, fine grain outputs are more frequent than coarse grain outputs. Note that a coarse grain output is required to restart a run. In this manual we refer to the fine grain output as monitoring. The time interval between two fine grain outputs is given by the real parameter DT. This time interval is sliced in as many smaller intervals as required to fulfill the Courant (or CFL) condition. Note that the last sub-interval may be smaller than what is allowed by the CFL condition, so that the time difference between two fine grain outputs is exactly DT. As for its predecessor FARGO, NINTERM fine grain outputs are performed for each coarse grain output, where NINTERM is an integer parameter. Fine grain outputs or monitoring may be used to get the torque onto a planet with a high temporal resolution, or it may be used to get the evolution of Maxwell’s or Reynolds’ stress tensor, or it may be used to monitor the total mass, momentum or energy of the system as a function of time, etc. The design of the monitoring functions in FARGO3D is such that a lot of flexibility is offered, and the user can in no time write new functions to monitor the data of his choice. The monitoring functions provided with the distribution can run on the GPU, and it is extremely easy to implement a new monitoring function that will run straightforwardly on the GPU, using the functions already provided as templates.

Flavors of monitoring¶

The monitoring of a quantity can be done in several flavors:

scalar monitoring, in which the sum (or average) of the quantity over the whole computational domain is performed. The corresponding output is a unique, two-column file, the left column being the date and the right column being the integrated or averaged scalar. A new line is appended to this file at each fine grain output.

1D monitoring, either in Y (i.e. radius in cylindrical or spherical coordinates) or Z (i.e. colatitude in spherical coordinates). In this case, the integral or average is done over the two other dimensions only, so as to get, respectively, radial or vertical profiles in each output. Besides, the 1D monitoring comes itself in two flavors:

a raw format, for which a unique file is written, in which a row of bytes is appended at every fine grain output. This file can be readily used for instance with IDL (using

openr&readucommands) or Python (using numpy’sfromfilecommand). For example, this allows to plot a map of the vertically and azimuthally averaged Maxwell’s tensor, as a function of time and radius. This map allows to estimate when the turbulence has reached a saturated state at all radii. In another vein, one can imagine a map of the azimuthally and radially averaged torque, which provides the averaged torque dependence on time and on z.a formatted output. In this case a new file is written at each fine grain output. It is a two-column file, in which the first column represents the Y or Z value, as appropriate, and the second column the integrated or averaged value. The simultaneous use of both formats is of course redundant. They have been implemented for the user’s convenience.

2D monitoring. In this case the integral (or averaging) is performed exclusively in X (or azimuth),so that 2D maps in Y and Z of the quantity are produced. In this case, a new file in raw format is written at each fine grain output.

Monitoring a quantity¶

Thus far in this section we have vaguely used the expression “the quantity”. What is the quantity and how is it evaluated?

The quantity is any scalar value, which is stored in a dedicated 3D

array. It is the user’s responsibility to determine an adequate

expression for the quantity, and to write a routine that fills, for

each zone, the array with the corresponding quantity. For instance, if

one is interested in monitoring the mass of the system, the quantity

of interest is the product of the density in a zone by the volume of

the zone. The reader may have a look at the C file

mon_dens.c. Toward the end of that file, note how the interm[]

array is precisely filled with this value. This array will further be

integrated in X, and, depending on what has been requested by the

user, possibly in Y and/or Z, as explained above. Note that the same

function is used for the three flavors of monitoring (scalar, 1D

profiles and 2D maps).

Monitoring in practice¶

We now know the principles of monitoring: it simply consists in having a C function that evaluates some quantity of interest for each cell. No manual averaging or integration is required if you program your custom function. But how do we request the monitoring of given quantities, what are the names of the corresponding files, and how do we include new monitoring functions to the code ? We start by answering the first question.

The monitoring (quantities and flavors) is requested at build time,

through the .opt file. There, you can define up to 6 variables, which

are respectively:

MONITOR_SCALAR

MONITOR_Y

MONITOR_Y_RAW

MONITOR_Z

MONITOR_Z_RAW

MONITOR_2D

Each of these variables is a bitwise OR of the different quantities of

interest that are defined in define.h around line 100. These

variables are labeled with a short, self-explanatory, uppercase

preprocessor variable.

For instance, assume that you want to monitor the total mass (scalar monitoring) and total angular momentum (also scalar monitoring), that you want to have a formatted output of the radial torque density, plus a 2D map of the azimuthally averaged angular momentum. You would have to write in your .opt file the following lines:

MONITOR_SCALAR = MASS | MOM_X

MONITOR_Y = TORQ

MONITOR_2D = MOM_X

Note the pipe symbol | on the first line, which stands for the

bitwise OR. It can be thought of as “switching on” simultaneously

several bits in the binary representation of MONITOR_SCALAR, which

triggers the corresponding request for each bit set to one. The

condition for that, naturally, is that the different variables defined

around line 100 in define.h are in geometric progression with a

factor of 2: each of them corresponds to a given specific bit set to

one. In our example we therefore activate the scalar monitoring of the

mass and of the angular momentum (we will check in a minute that

MOM_X corresponds to the angular momentum in cylindrical and

spherical coordinates). This example also shows that a given variable

may be used simultaneously for different flavors of monitoring:

MOM_X (the angular momentum) is used both for scalar monitoring

and 2D maps.

The answer to the second question above (file naming conventions) is as follows:

Unique files are written directly in the directory

monitor/fluidnameinside the output directory (e.g.outputs/fargo/monitor/gas/). Their names have a radix which indicates which quantity is monitored (e.g.mass,momx, etc.), then a suffix which indicates the kind of integration or averaging performed (_1d_Z_rawor_1d_Y_raw, or nothing for scalar monitoring) and the extension.dat.Monitoring flavors that require new files at each fine grain output do not write the files directly in the output directory, in order not to clutter this directory. Instead, they are written in subdirectories which are named

FG000..., like “Fine Grain”, plus the number of the current coarse grain output, with a zero padding on the left. In these directories, the files are written following similar conventions as above, plus a unique (zero padded) fine grain output number. It is a good idea to have a look at one of the outputs of the public distribution (choose a setup that requests some monitoring, by looking at its.optfile), in order to understand in depth these file naming conventions.Some monitoring functions depend on the planet (such as the torque). In this case, the code performs automatically a loop on the different planets and the corresponding file name has a suffix which indicates in a self-explanatory manner the planet it corresponds to.

How to register a monitoring function¶

You may now stop reading if you are not interested in implementing your own monitoring functions, and simply want to use the ones provided in the public distribution.

However, if you want to design custom monitoring functions for your

own needs, let us explain how you include such functions to the

code. Let us recall that a monitoring function is a function that

fills a dedicated 3D arrays with some value of interest, left to the

user. This function has no argument and must return a void. Have a

look at the the file mon_dens.c and the function void

mon_dens_cpu() defined in it. Note that the temporary array

dedicated to the storage of the monitoring variable is the Slope

array. As we enter the monitoring stage after a (M)HD time step, the

Slope array is no longer used and we may use it as a temporary

storage. Any custom monitoring function will have to use the

Slope array to store the monitoring variable.

The monitoring function is then registered in the function

InitMonitoring() in the file monitor.c. There, we call a

number of times the function InitFunctionMonitoring () to register

successively all the monitoring functions defined in the code.

The first argument is the integer (power of two) that is associated to the function, and which we use to request monitoring at build time in the

.optfile.The second argument is the function name itself (the observant reader will notice that this is not exactly true: in

mon_dens.cthe function ismon_dens_cpu(), whereas inInitMonitoring()we have:InitFunctionMonitoring (MASS, mon_dens, "mass",...instead of:

InitFunctionMonitoring (MASS, mon_dens_cpu, "mass",...

The reason for that is that mon_dens is a function pointer itself,

that points to mon_dens_cpu() or to mon_dens_gpu(), depending

of whether the monitoring runs on the CPU or the GPU).

The third argument is a string which constitutes the radix of the corresponding output file.

The fourth argument is either

TOTALorAVERAGE(self-explanatory).The fifth argument is a 4-character string which specifies the centering of the quantity in Y and Z. The first and third characters are always respectively Y and Z, and the second and fourth characters are either S (staggered) or C (centered). This string is used to provide the correct values of Y or Z in the formatted 1D profiles. For instance, the zone mass determined in

mom_dens.cis obviously centered both in Y and Z.The sixth and last argument indicates whether the monitoring function depends on the coordinates of the planet (

DEP_PLANET) or not (INDEP_PLANET). In the distribution provided only thetorqfunction depends on the planet.

The call of the InitFunctionMonitoring() therefore associates a

variable such as MASS or MAXWELL to a given function. It

specifies the radix of the file name to be used, and gives further

details about how to evaluate the monitored value (loop on the

planets, integration versus averaging, etc.) We may now check that

requesting MOM_X in any of the six variables of the .opt file

does indeed allow a monitoring of the angular momentum. We see in

InitMonitoring() that the MOM_X variable is associated to

mon_momx(). The latter is defined in the file mon_momx.c where

we can see that in cylindrical or spherical coordinates the quantity

evaluated is the linear azimuthal velocity in a non-rotating frame,

multiplied by the cylindrical radius and by the density.

Implementing custom monitoring: a primer¶

In this distribution, we adhere to the convention that monitoring

functions are defined in files that begin with mon_. If you define

your own monitoring function and you want it to run indistinctly on

the CPU or on the GPU, you want to define in the mon_foo.c file

the function:

void mon_foo_cpu ()

then in global.h you define a function pointer:

void (*mon_foo)();

In change_arch.c this pointer points either to the CPU function:

mon_foo = mon_foo_cpu;

or to the GPU function:

mon_foo = mon_foo_gpu;

depending on whether you want the monitoring to run on the CPU or the

GPU. Finally, the syntax of the mon_foo.c file must obey the

syntax described elsewhere in this manual so that its content be

properly parsed into a CUDA kernel and its associated wrapper, and the

object files mon_foo.o and mon_foo_gpu.o must be added

respectively to the variables MAINOBJ and GPU_OBJBLOCKS of the

makefile. A good starting point to implement your new

mon_foo_cpu() function is to use mon_dens.c as a template.

Both the _cpu() and _gpu() functions need to be declared in

prototypes.h:

ex void mon_foo_cpu(void);

in the section dedicated to the declaration of CPU prototypes, and:

ex void mon_foo_gpu(void);

in the section dedicated to the declaration of GPU prototypes. Be sure

that the declaration is not at the same place in the file. The second

one must be after the #ifndef __NOPROTO statement

In order to be used, you new monitoring function needs to be

registered inside the function InitMonitoring () of the file

monitor.c, using a syntax as follows:

InitFunctionMonitoring (FOO, mon_foo, "foo", TOTAL, "YCZC", INDEP_PLANET);

or similar, as described above. In this sentence, FOO is an

integer power of 2 that must be defined in define.h. Be sure that

it is unique so that it does not interfere with any other predefined

monitoring variable. You are now able to request a fine grain output

of your ‘’foo’’ variable, using in the .opt file expressions such

as:

MONITOR_SCALAR = MASS | FOO | MOM_Z

MONITOR_2D = BXFLUX | FOO